I would like to examine David Hokney’s (1937) famous 1967 painting A Bigger Splash, pretending to know nothing about the author’s life and analysing only the formal and chromatic elements in the painting. Convinced that an author of visual texts expresses everything he has to tell us through the grammatical elements of his discipline and that, in Hokney’s case, we find in the painting, within which unconscious elements of his personality, as well as of ours as observers, could also be hidden. When we look at an image, we read it from our own point of view, projecting our own sensitivity, our own experience into it, so that each viewer reconstructs the picture with the author each time. In my opinion, this is the marvellous aspect of art: first of all, through it we strive to look at the world through the eyes of the author, but at the same time we give that work particular nuances that will make it different from observer to observer, so that with each viewing the work is regenerated, as is our way of looking at the world; through it we establish a dialogue with the author that assigns us a role of participation and not just of spectator.

I would therefore like to read the work from the viewer’s point of view, who may well never have even heard of Hokney, nor have any particular interest in painting, but who, on visiting the Tate Gallery and coming across the painting, will necessarily receive emotional states from it; states suggested by the shapes, the composition and the colours, both in the type of hues chosen by the artist and in the way they are applied to the surface. The historian will certainly relate the painting he is looking at to the artist’s other works, to his biographical events and to the historical, social and artistic context in which the painting was executed. Aspects that the spectator does not necessarily take into account and is not obliged to know. Just as when attending a performance of Symphony No. 9 in D minor in a theatre, or listening to an engraving of it, the listener may not necessarily be familiar with other works by Beethoven or know anything about his life or even the historical period in which he lived. This does not detract from the fact that the listener hearing that musical structure, made up of those musical movements and those particular sounds, is pervaded by the emotional state generated by it. The examples could be extended to every artistic discipline and, after all, therein lies the wonder of artistic expression itself. Art conveys what it ‘has to say’ through an emotional and not a rational relationship. The rationalisation of language is an aspect that concerns the enthusiast or the technician of the discipline, who, for his or her own personal or professional interest, will go into its linguistic and historical aspects in greater depth.

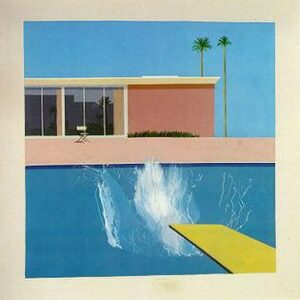

And so we come to A Bigger Splash. Hokney shows us a Californian-style villa with a swimming pool that reminds us of Hollywood cinema and its stars, perhaps because of the director’s chair by the pool or perhaps because we have seen such villas countless times in those very films.

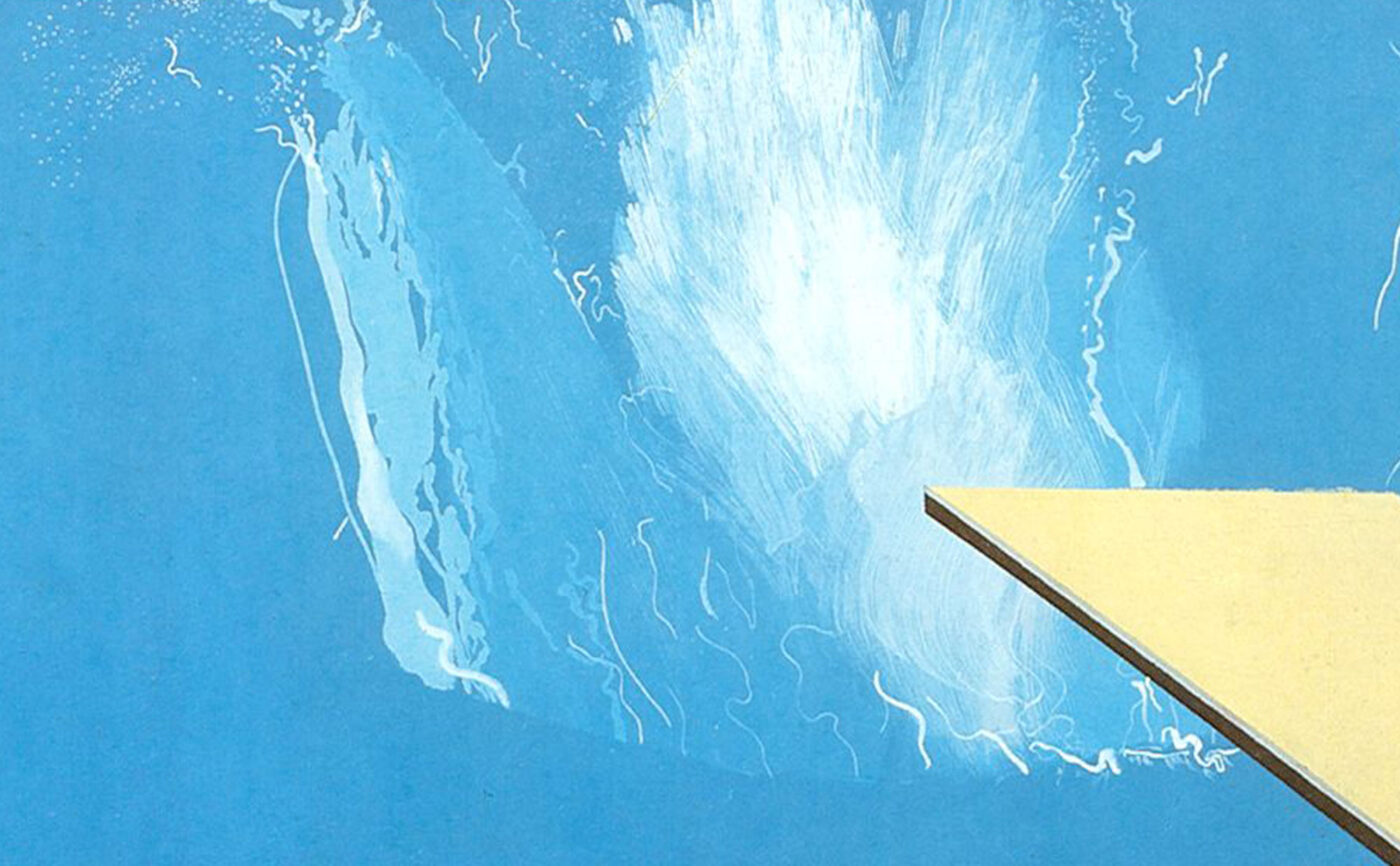

In any case, the villa and swimming pool are shown frontally, absolutely flat, as are the acrylic colours, which Hokney prefers because of the two-dimensional backgrounds and cool tones that this technique provides. The pictorial space is pervaded by the blues of the sky and water, while the villa and poolside are characterised by pinkish hues strongly lightened by the white, which cools them down by attenuating the red component. Thus the trampoline of a brown rich in yellow, also faded by the white, seems to be cooling down. The predominant compositional directionality is horizontal, which, added to the coldness and two-dimensionality of the form and colour, gives the work a temporal suspension and an absence that is also emphasised by the emptiness of the chair, the diving board and the splash of water caused by a non-existent diver. The horizontal stasis of the villa and the poolside is broken by the diagonal entrance of the diving board. This entrance from the bottom right surprisingly breaks through the immobility of the image, like a stone thrown onto the flat surface of the water.

Something has come to disturb the stasis of that microcosm, a metaphor for a class and a social model of reference in the common imagination. A dream that shatters, a status that decays. It is precisely the splash of water that makes the rest appear so immobile and empty. We are faced with two readings: on the one hand, the shattered dream, and on the other, that of a decayed imaginary, whose signs of vitality (the splash of water) are now a pale memory of something that has already happened (the diver’s absence), that has taken place but that we have not witnessed or participated in, and we observe the consequences.

The formal appearance of an advertising illustration or an American magazine from the 1940s, where everything is synthesised and geometrical, not only the villa but also the palm trees that look more like cocktail sticks than plants, persuade us even more by referring to the Hollywood glitz of times gone by.

Here, then, is a surprising aspect of painting, where a landscape can convey a global historical and social context, at least in an imagery standardised by cinema and now shared everywhere. A judgement that leads one to reflect on the state of this imagery and the society that produces it. And, where, the answer is generated individually through the dialogue with the author triggered by his work.

David Hokney, A bigger splash, 1967, acrylic on canvas 242,5 × 243,9 cm, Tate gallery, London

Bibliography

ARNHEIM Rudolf, Arte e percezione visiva, [1954], Milano, Feltrinelli, 2002.

CAROLI Flavio, Magico primario, Milano, Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri, 1982.

COSTA Antonio, Il cinema e le arrti visive, Torino, Einaudi, 2002.

DE GRANDIS Luigina, Teoria e uso del colore, Milano, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1984.

DE MICHELI Mario, Le avanguardie artistiche del Novecento, [1986], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1988.

FALCINELLI Riccardo, Cromorama, Torino, Einaudi Editore, 2017.

GOMBRICH, Ernst H. HOCHBERG Julian BLACK Max, Arte percezione e realtà, [1972], Torino, Einaudi, 2002.

ITTEN Jhoannes, Arte del colore, [1961], Milano, Il Saggiatore, 2001.

SWEENEY Michael S., Dentro la Mente – La sorprendente scienza che spiega come vediamo, cosa pensiamo e chi siamo,, Vercelli, Edizioni White Star (per l’Italia), National Geographic Society, 2012.

TORNAGHI Elena, Il linguaggio dell’arte, [1996], Torino, Loescher, 2001.

Website