If I have to think of a particularly significant illustrator, an illustrator who best represents the alphabetical development of illustration and its language, then I think of Jean-Ignace-Isidore Gérard (1803-1847), better known as Grandville, whose work I consider to be the constitutive root of different imaginative universes to come. Grandville brings together the distorting heritage of the caricature tradition, which began with Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) in the early 17th century, with Giovan Battista Bracelli (1584-1650) and which can be traced back as far as Leonardo’s humorous drawings.

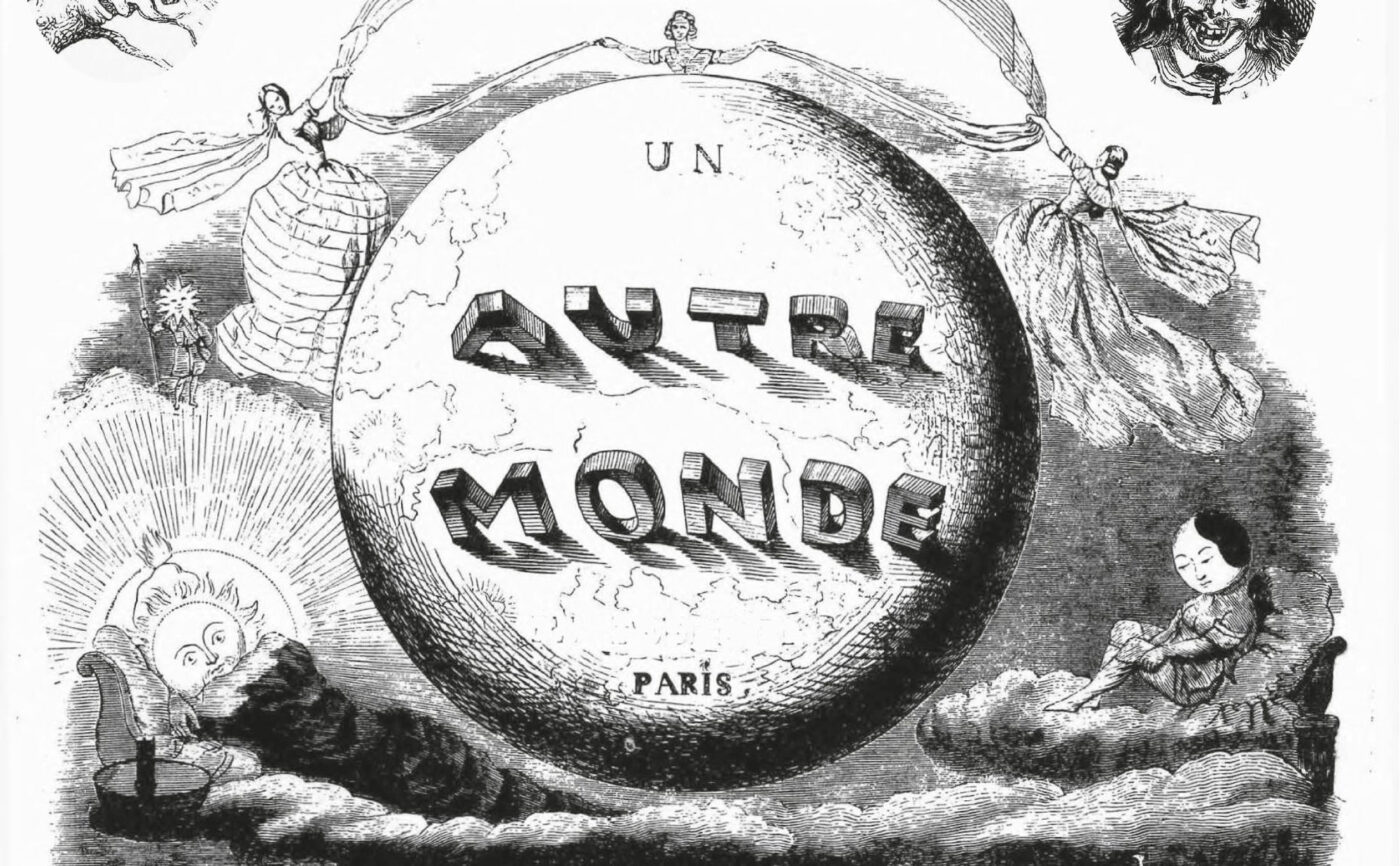

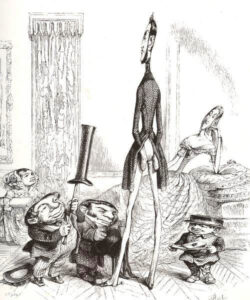

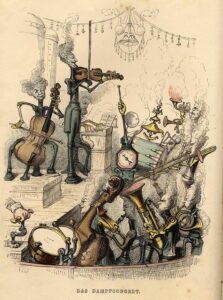

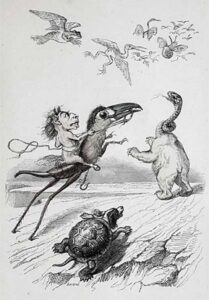

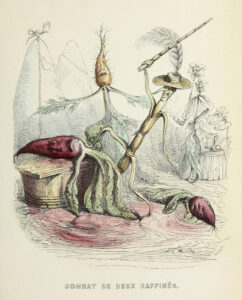

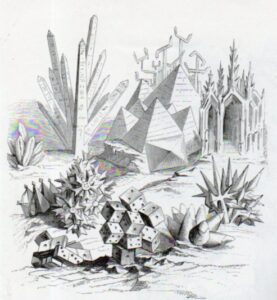

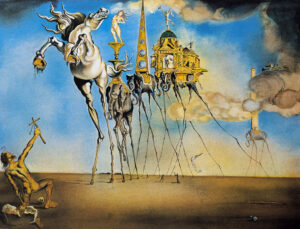

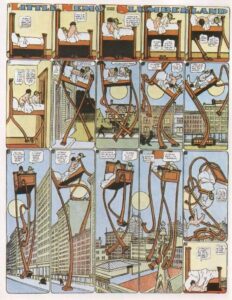

Grandville takes up the distorting heritage of the caricature tradition and pushes it to visionary consequences, some of which are already in the pipeline and others never seen before. In Grandville’s illustrations, outstanding technical skill is combined with boundless imagination, which in a work like Autre Monde (1844) appears inexhaustible and precursor. We can see human and animal anatomical disproportions, animated and anthropomorphic objects, anthropomorphic plants, anthropomorphic animals, human anatomies subjected to the lengthening or shrinking of a funfair hall of mirrors, disproportions between characters reminiscent of medieval painting, forced unprecedented framing, composite animals reminiscent of bestiaries and classical epics, pre-surrealist settings for which the reader’s memory cannot but go to Magritte (René Magritte 1898-1967) or Dalì (Salvador Dalì 1904-1989) or the metaphysical landscapes of Alberto Savinio (1891-1952). Some of his anatomical elongations or disproportions and a certain anthropomorphism also certainly marked the work of the two great Surrealists. We can also find indelible traces of this in the imaginative world of Little Nemo, a comic strip created by Windsor McCay (1869-1934) in 1905, which narrates the dreamlike adventures of a child with a very elegant Art Nouveau style and an inexhaustible imagination typical of childhood.

If we then look at a work such as Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (1840-42) by Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850), it is practically impossible not to consider it a forerunner of all those universes, animated or cartoon, inhabited by anthropomorphic animals, Disney in the lead, but passing through the illustrated universe of Potter (Beatrix Potter 1866-1943). Grandiville’s work certainly still retains the typical flavour of engraving and a realism, albeit caricatured and grotesque, of a classical matrix, but it is clear that the French illustrator sowed countless seeds for future, flourishing imagery that would cross over into painting, cinema, animation, humorous cartoons and comics. In this sense, I believe that Grandville’s is to be considered one of the most prolific imaginations in the history of illustration, which, with wisdom and skill, took many inheritances from the bestiaries, from the demonic inventions of Flemish painting, from the grotesques, from the whims and eccentricities of the Baroque, transforming them into something unprecedented that would indelibly mark much of the popular and cultured production with unexpected consequences that are still ongoing. It must be said that in the years in which Grandiville worked there was still no clear separation between painting and illustration and this allowed him a freedom of action, both formal and imaginative, that is unknown today.

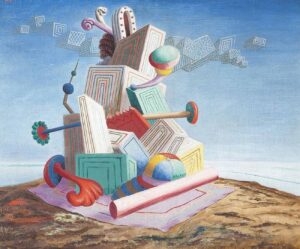

Grandville, 5 engravings from Autre Mode; Salvador Dali, The Temptation of St. Anthony; 1946, Windsor McCay, Little Nemo, 1908; Alberto Savinio, Tombeau d’un roi maure, 1929

Grandville, 5 engravings from Autre Mode; Salvador Dali, The Temptation of St. Anthony; 1946, Windsor McCay, Little Nemo, 1908; Alberto Savinio, Tombeau d’un roi maure, 1929

Bibliografia

AA.VV., Desideri in fiorma di nuvole. Cinema e fumetto, Paisan di Prato (UD), Campanotto Editore, 1996.

AA.VV., Gulp! 100 anni a fumetti, Milano, Electa, 1996.

BAIRATI Eleonora – FINOCCHI Anna, Arte in Italia, volume 3, [1984], Torino, Loescher Editore, 1991.

BARBIERI Daniele, I linguaggi del fumetto, Milano, Bompiani, 1991.

BORDONI Carlo FOSSATI Franco, Dal feuilleton al fumetto. Generi e scrittori della letteratura popolare, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

BRANCATO Sergio, Fumetti. Guida ai comics nel sistema dei media, Roma, Datanews Editrice, 1994.

COSTA Antonio, Il cinema e le arrti visive, Torino, Einaudi, 2002

DE VECCHI Pierluigi CERCHIARI Elda, Arte nel tempo, [1991], Milano, Bompiani, 1996.

DE VINCENTI Giorgio, Andare al cinema, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

FAETI Antonio, Guardare le figure, [1972], Roma, Donzelli Editore, 2011.

FARNÉ Roberto, Iconologia didattica – le immagini per l’educazione dell’Orbis Pictus a Sesame Street, [2002], Bologna, Zanichelli Editore, 2006.

FAVARI Pietro, Le nuvole parlanti. Un secolo di fumetti tra arte e mass media, Bari, Edizioni Dedalo, 1996.

FRESNAULT-DERUELLE Pierre, I fumetti: libri a strisce, [1977], Palermo, Sellerio Editore, 1990.

PALLOTTINO Paola, Storia dell’illustrazione italiana, [2010], Firenze, VoLo Publisher, 2011.

PELLITTERI Marco, Sense of comics, Roma, Castelvecchi, 1998.

RAFFAELI Luca, Il fumetto, Milano, il Saggiatore, 1997.

REY Alain, Spettri di carta, [1982], Napoli, Liguori, 1988.

RICCIARDI Enrica, Il cuore delle nuvole. Arte figurativa e fumetto, Paisan di Prato (UD), Campanotto Editore, 1996.

Siti web