Seminar held on 7 November 2020 at the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Jesi, as part of the cycle entitled Interventi intorno Chiari

The Contemporary Era

I would like to start with some remarks on Chiari’s work (Giuseppe Chari 1926-2007), for which the references to the New Dada experience are indispensable, with particular reference to Rauschenberg’s research (Robert Rauschenberg 1925-2008), which, in turn, looks back to the original Dada and to Schwuitters’ assemblages (Kurt Schwitters 1887-1948) and to some of Duchamp’s pre-conceptual experiences (Marcel Duchamp 1887-1968). The Dada current belongs to the so-called historical avant-garde movements that marked the first thirty years of the 20th century. References to the experiences of European Informal Art and American Abstract Expressionism would also be indispensable, but to say this would be to say nothing to those who are not accustomed to art-historical events. Chiari’s – like many contemporary artistic languages – is a complex and stratified alphabet, which can be traced back to the so-called Italian Neo-avant-garde movements of the 1960s and 1970s, belonging to the broader historical moment defined as Postmodern.

Chiari’s work should be seen in the context of the so-called neo-avant-gardes, which succeeded neo-realism, to which they were opposed, and which in Italy coincided above all with the work of the Gruppo ’63 and were also part of the wider international context defined as post-modern.

It is therefore necessary to understand the formation and spirit of that historical context, which is necessary to read its expressive declinations.

Postmodernity, as its name declares, follows and arises as a response to modernism, which constitutes one of the multiple phases of the broader body that we call the Contemporary Era. An epoch that was determined during the eighteenth century and whose birth coincides for convenience with the French Revolution of 1789.

1658 Comenius’ Orbis sensualium pictus

1670-74 Colour Spectrum and 1687 Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (on Gravity and the Principles of Dynamics) Isaac Newton

1688 Parliamentary monarchy born in England

1738 Start of excavations at Herculaneum and in 1748 at Pompeii, which were to have great influence on the birth of Neoclassicism and marked the birth of Archaeology

1751-80 Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers Diderot with the collaboration of d’Alembert

1765-74 first industrial revolution in cotton textiles, flying spool

1765-85 Sturm und Drang pre-Romantic movement

1760 Songs of Ossian and 1765 The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole

1783 Birth of Ethnology and in 1799 the Society of Human Observers and then Anthropology in Paris.

1789 Contemporary Era that for convenience coincides with the French Revolution, but that also includes the first industrial revolution

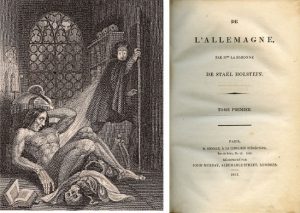

1813 Madame de Staël’s De l’Allemagne, a work that is generally recognised as the beginning of Romanticism.

1814 Restoration

1848 Manifesto of the Communist Party in which Marx and Engels separate “utopian socialism” from “scientific socialism”, i.e. communism

1848 Risorgimento literary naturalism and realism in painting can also be traced back to this period

1859 Darwin’s The Origin of Species

1870 Second Industrial Revolution introduction of electricity, oil and chemicals

1880 ca. Modernism mainly linked to Art Nouveau, but the movement included many elements: Symbolist poetry, decadentism, Wagner, postimpressionism, William Morris’ Arts and Crafts

1886 Symbolist Manifesto movement that began in the middle of the century at the instigation of Baudelaire.

1896 Bergson’s Matter and Memory

1899 Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams

1914-18 First World War

1914 Kafka’s The Trial and Joyce’s Dubliners, 1913 Proust’s On Swann’s Side, 1912 Mann’s Death in Venice, 1923 Svevo’s The Conscience of Zeno.

1920 To this decade belong the first productions of Edgar Varese in which he eliminates the difference between sound and noise giving start to the Concrete and Electronic music, through a chaotic percussionism and pre-recorded sounds, already before Charles Ives had contaminated the classical music with the American popular productions (gospel, regtime, country, band)

1921 Einstein’s theory of general relativity (proposed a relativistic theory of gravitation as early as 1915)

1939-45 Second World War

1970 Third Industrial Revolution computer science, electronics and telecommunications

1971 Information Age succeeded the Industrial Age and was characterised by the extreme speed at which information was transferred and became the main economic product, giving rise to the Intangible Economy.

It was at this moment in history that society as we know it today emerged, the result of a radical social and economic change. The bourgeois class was born, which slowly supplanted the aristocratic class, giving rise to the democratic model. This process was made possible by the first industrial revolution, which enabled the economic emancipation of the bourgeoisie from the power of the nobility.

Left: Anonymous, The people of Paris storming the Bastille fortress, 14 July 1789 Right: William Pickett: Ironworks at Caaldbrookdale, 1805

It was thanks to the Enlightenment and positivist thinking that ran through that entire century that the social and industrial revolutionary impulse was determined, and also manifested itself through the birth of some of the typical subjects of our modern thinking. The focus on education and the child as a social subject led to the start of schooling. Comenius’ Orbis Pictus (Giovanni Amos Comenius 1592-1670), the forerunner of all abecedaries and the starting point for pedagogy, dates back to the middle of the previous century.

John Amos Comenius Orbis Sensualium Pictus 1658 (Theologian and pedagogue who wrote what is considered to be the first book for children, with the use of illustration aimed at learning to read and thus the birth of pedagogy)

Museums were born, also aimed at disseminating knowledge, information periodicals, the encyclopaedia and new disciplines were introduced: such as archaeology, following excavations at Herculaneum in 1738 and then at Pompeii in 1748; or such as ethnology born in 1786 and then anthropology with the foundation in Paris of the Society of the Observers of Man in 1799, which paid scientific attention to non-European cultures, albeit accompanied by colonialism.

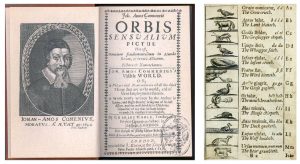

Encyclopédie ou dictionaire raissoné des sciences, des artes et des métieres, written and edited by Diderot in collaboration with D’Alembert and a large number of collaborators, comprising 28 volumes, 11 of which are illustrated plates, and which took twenty years to be published, starting in 1751. Dissemination of knowledge – Schooling – Children become social subjects in which to invest.

In addition, Jan-Charles Pellerin founded a printing company in Épinal in 1796, the work of which is at the heart of the imagerie populaire, so much so that it coincides with the name given to its production, Imagerie d’Épinal. Pellerin’s production of images was distributed throughout Europe, organised industrially by genre and even survived until the 1980s, a large part of which was dedicated to the world of children and the forerunner of the modern merchandising found on newsstands today. They included figurines of characters to cut out and assemble, models that could also be cut out and assembled, board games, illustrated fairy tales and, of course, religious images (the basis of future holy cards) or satirical images of characters and events of the time. His first production consisted of paper toy soldiers with their weapons from the Napoleonic campaigns, but, even in this case, those toy soldiers were only the progenitors of later productions in lead and then in plastic.

Left: Hoffbauer, Exposition des produits de l’industrie française, dans la cour du Louvre, 1801. Center: N. 1 de Le Charivari, 1 dicembre 1832. Right: Imagerie d’Épinal. Nascita dei Musei (il 10 agosto del 1793 nasce il Louvre)

– Birth and expansion of satirical and news magazines

– Impetus for the massive use of illustrative images

– Evolution of printing techniques (woodcut and later lithography), allowing more and more copies to be printed at lower cost.

– In 1796, Jean-Charles Pellerin founded a printing house in Épinal, which became a real industry for printing and distributing images, giving rise to the so-called Imagerie d’Épinal, which is at the basis of the popular figurative imagination.

Left: Imaginary reconstruction of Herculaneum. Right: Watercolour engraving documenting ethnological explorations.

– Birth of archaeology in 1738 following excavations at Herculaneum and later, in 1748, at Pompeii

– Birth of ethnology in 1783

– Of Crimes and Punishments 1764 by Cesare Beccaria

– Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, Virginia 1773 first institution for the mentally ill

– The use of soap spreads, leading to an increase in average life expectancy.

William Hogarth, The Bedlam Asylum, 1733

That era thus saw, on the one hand, a modern sentiment aimed at progress and social evolution and, on the other, the economic root of capitalism on which it was based and whose reasons and needs were already then opposed to an excess of emancipation. A dichotomy that characterised all subsequent history, becoming a typical feature of contemporary life. It was in the 18th century that the land register was born and with it the concept of private property. And it was also in that century that the literary genre of bourgeois entertainment was born. It began with the Gothic novel, with its fears and dark atmospheres, dictated precisely by the excess of rationalism and social mechanisation and, in part, anticipated by Ossian’s Songs of 1760. It was precisely in these fledgling periodicals that literary genres and the massive use of images to illustrate both pieces of fiction and pieces of information became widespread. From then on, the use of images became unstoppable and grew exponentially, resulting in another typical contemporary feature.

Left: François Vivares: View of the surface works at Colbrookdale, 1758. Right: Joseph Wright,View of Cromford c. 1793.

– Mechanisation of work

– Disruption of habits linked to natural cycles

– Disruption of the suburban landscape

– The reaction to these three aspects determines the birth of the Gothic novel.

– 1764 The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole

– 1818 Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley is published

– 1819 John William Polidori’s short story The Vampire is published in the New Monthly Magazine.

– 1872 Carmilla by Sheridan Le Fanu

– 1897 Dracula by Braham Stoker

The starting point for Gothic literature is Horace Walpole’s (1717-1797) The Castle of Otranto of 1764, but certainly the best known novel of the genre is Mary Shelley’s (1797-1851) Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus of 1818. This book contains the seeds of what would later become horror and future science fiction, where the monster, who comes to life thanks to lightning, embodies a nature that rebels against the delirious excesses of scientific reasoning represented by Dr Frankenstein himself. In the meantime the sentimental novel had already emerged with the works of Samuel Richardson (1689-1761), of which Pamela or the Recognised Virtue of 1741 and Clarissa of 1747 are the two best known works, defining the figures of the heroine, in the first, and the anti-heroine, in the second. In 1791, with Justine or the misfortunes of virtue by the Marquis de Sade (Donatien-Alphonse-François de Sade 1740-1814), the libertine novel came to life. In 1841, The Crimes of the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) appeared in a Philadelphia periodical, the progenitor of the detective genre, although still deeply imbued with the typical Gothic characters assigned to it by the murderous gorilla. The modern detective novel is generally traced back to 1868 with Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone. The social novel, on the other hand, began with universally known titles and authors: The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870), both in 1844; Victor Hugo’s (1802-1885) Les Miserables in 1862. The protagonists of this genre are bourgeois who, despite having suffered profound injustices, are able to redeem themselves thanks to their heroic and superhuman strength of will, a heroism that has the characteristics of what in the decadentist era became Nietzsche’s superhumanism. Meanwhile, in 1864, Jules Verne’s (1828-1905) Journey to the Centre of the Earth was published, the forefather of science fiction, while Herbert George Wells’ (1866-1949) Time Machine was published in 1895.

When Romanticism was born in 1813, with the publication of De l’Allemagne by Madame de Staël (Anne-Louise Germaine Necker, Baroness of Staël-Holstein 1766-1817), it brought with it elements typical of the Enlightenment’s impulse towards emancipation, as well as the more obscure characteristics that had become apparent with the Gothic, and a great attention to the discovery of the national roots of the various European countries. This last aspect, which towards the end of the century, with the unrealistic attitudes of decadentism and symbolism, would change into nationalism.

Also within the 19th century body of thought were the great social movements that responded to the increasing pressure from the development of industry and capitalism. Thus, first came utopian socialism and, in 1848, scientific socialism, which Marx (1818-1883) and Engels (1820-1895) referred to as communism.

Theodore Von Holst, illustration from the inside cover of the 1831 edition of Frankenstein.

– Romance novel 1741 Pamela or virtue acknowledged and in 1747 Clarissa by Samuel Richardson

– Libertine novel 1791 Justine or the misfortunes of virtue by the Marquis de Sade

– Social Novel 1844 The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, 1862 Les Miserables by Victor Hugo

– 1841 The Crimes of the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe , Modern detective story 1868 The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins

– Science Fiction 1864 Journey to the Centre of the Earth by Jules Verne, 1895 The Time Machine by Herbert George Wells

– Romanticism brought with it both elements typical of the Enlightenment, such as the impulse towards emancipation, and the darker characters that had made their way into the Gothic.

– Romanticism also paid a great deal of attention to the discovery of the national roots of the various European countries, an aspect that by the end of the century, with the unrealistic attitudes of decadentism and symbolism, would change into nationalism.

– 1813 Madame de Staël’s De l’Allemagne, a work that is generally recognised as the beginning of Romanticism.

– 1815-48 Popular movements

– The 1940s saw the development of Realist painting

– 1848 Springtime of the Peoples

– 1848 Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (differentiates utopian socialism from scientific socialism or communism)

– 1842 La Comédie humaine by Honoré de Balzac

– From the 1950s onwards literary Naturalism develops

– 1859 The Origin of Species by Charles Darwin

In 1870, following the introduction of oil and electricity, the second industrial revolution took place, which gave new impetus to the technologies used by industry. Ten years later, modernism was born, mainly characterised by the Art Nouveau taste, but which brought within itself the already mentioned decadentism and symbolism, the latter having already gained momentum with Baudelaire in the middle of the century. It was precisely the vague and contemptuous attitudes towards the bourgeoisie of these two currents, even though they still coexisted with the impulse towards civil emancipation, that led within a few years to the nationalisms that were made concrete in the following century by Fascism and Nazism. Moreover, both currents picked up the dark legacy born of the Gothic movement and, looking back, its omens already seem to warn of the precipice of the First World War and its devastation.

William Morris

– 1870 Second Industrial Revolution Introduction of electricity, oil and chemicals

– 1874 Impressionism

– 1875 Literary verism

– 1880 ca. Modernism

mainly linked to Art Nouveau, but the movement includes many elements:

– 1886 Symbolist manifesto, Symbolist poetry has its progenitor in Baudelaire already in the middle of the century

– Decadentism

– Wagner

– Post-impressionism

– William Morris’ Arts and Crafts

Bibliography

AA.VV., Desideri in fiorma di nuvole. Cinema e fumetto, Paisan di Prato (UD), Campanotto Editore, 1996.

AA.VV., Gulp! 100 anni a fumetti, Milano, Electa, 1996.

AA.VV., Nuovo fumetto italiano, Milano, Fabbri Editori, 1991.

ANTOCCIA Luca, Il viaggio nel cinema di Wim Wenders, Bari, Dedalo Edizioni, 1994.

ARGAN Giulio Carlo, L’arte moderna 1770/1970, [1970], Firense, Sansoni Editore, 1982.

ARNHEIM Rudolf, Arte e percezione visiva, [1954], Milano, Feltrinelli, 2002.

AUMONT Jacques MARIE Michel, L’analisi dei film, [1988], Roma, Bulzoni Editore, 1996.

BAIRATI Eleonora – FINOCCHI Anna, Arte in Italia, volume 3, [1984], Torino, Loescher Editore, 1991.

BARBIERI Daniele, I linguaggi del fumetto, Milano, Bompiani, 1991.

BARILLI Renato, Il cilclo del postmoderno. La ricerca artistica degli anni’80, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1987.

BARILLI Renato, Informale oggetto comportamento 1. La ricerca artistica negli anni’50 e’60, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1979.

BONITO OLIVA Achille, L’ideologia del traditore – Arte, maniera, manierismo, [1976], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1981.

BORDONI Carlo FOSSATI Franco, Dal feuilleton al fumetto. Generi e scrittori della letteratura popolare, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

BOSCHI Luca, Frigo valvole e balloons. Viaggio in vent’anni di fumetto italiano d’autore, Roma-Napoli, Edizioni Theoria, 1997.

BOURRIAUD Nicolas, Il radicante, [2009], Milano, Postmedia, 2014.

BRANCATO Sergio, Fumetti. Guida ai comics nel sistema dei media, Roma, Datanews Editrice, 1994.

CALVESI Maurizio, Le due avanguardie. Dal Futurismo alla Pop Art, Bari, Laterza, 1991.

CARA Giovanni, Scrittori e popelin, Civitanova Marche, Gruppo Editoriale Domina, 2003.

CAROCCI Giampiero, Elementi di storia – L’Età delle rivoluzioni borghesi, volume 2, [1985], Bologna, Zanichelli, 1990.

CAROLI Flavio, Magico primario, Milano, Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri, 1982.

CASETTI Francesco DI CHIO Federico, Analisi del film, Milano, Bompiani, 1990.

COSTA Antonio, Il cinema e le arrti visive, Torino, Einaudi, 2002.

DEBENEDETTI Giacomo, Il Romanzo del Novecento, [1971], Milano, Garzanti Editore, 1989.

DEL GIUDICE Daniele, Staccando l’ombra da terra, Milano, Edizione CDE, 1994.

DEL GUERCIO Antonio, Storia dell’arte presente, Roma Editori Riuniti, 1985.

DE MICHELI Mario, Le avanguardie artistiche del Novecento, [1986], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1988.

DE VECCHI Pierluigi CERCHIARI Elda, Arte nel tempo, [1991], Milano, Bompiani, 1996.

DE VINCENTI Giorgio, Andare al cinema, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

DORFLESS Gillo, Ultime tendenze nell’arte d’oggi, [1961], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1985.

FAETI Antonio, Guardare le figure, [1972], Roma, Donzelli Editore, 2011.

FARNÉ Roberto, Iconologia didattica – le immagini per l’educazione dell’Orbis Pictus a Sesame Street, [2002], Bologna, Zanichelli Editore, 2006.

FAVARI Pietro, Le nuvole parlanti. Un secolo di fumetti tra arte e mass media, Bari, Edizioni Dedalo, 1996.

FRESNAULT-DERUELLE Pierre, I fumetti: libri a strisce, [1977], Palermo, Sellerio Editore, 1990.

FREZZA Gino, La scrittura malinconica. Sceneggiatura e serialità nel fumetto italiano, Firenze, La Nuova Italia, 1987.

GUGLIELMINO Salvatore, Guida al novecento, [1971], Milano, Editrice G. Principato s.p.a., 1982.

HARVEY David, La crisi della modernità, [1990], Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1997.

HONNEF Klaus, L’arte contemporanea, Köln, Taschen, 1990.

HUGHES Robert, Lo shock dell’arte moderna, Milano, Idealibri, 1982.

KUBLER George, La forma del tempo, [1972], Torino, Einaudi, 1989.

LYOTARD Jean-François, La condizione postmoderna, [1979], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1990.

LYOTARD Jean-François, Peregrinazioni. Legge, forma, evento, [1988], Bologna, Il Mulino, 1992.

MALTESE Corrado, Guida allo studio della storia dell’arte, [1975], Milano, Mursia, 1988.

MALTESE Corrado, Storia dell’arte in Italia 1785-1943, [1960], Torino, Einaudi, 1992.

MENNA Filiberto, La linea analitica dell’arte moderna, [1975], Torino, Einaudi, 1983.

MILA Massimo, Breve storia della musica, [1963], Torino, Einaudi, 1993.

MONTANER Josep Maria, Dopo il movimento moderno. L’architettura della seconda metà del Novecento, [1993], Roma, Laterza, 1996.

PALLOTTINO Paola, Storia dell’illustrazione italiana, [2010], Firenze, VoLo Publisher, 2011.

PELLITTERI Marco, Sense of comics, Roma, Castelvecchi, 1998.

PRIGOGINE Ilya, Le leggi del caos, Bari, Laterza, 1993.

RAFFAELI Luca, Il fumetto, Milano, il Saggiatore, 1997.

REY Alain, Spettri di carta, [1982], Napoli, Liguori, 1988.

RICCIARDI Enrica, Il cuore delle nuvole. Arte figurativa e fumetto, Paisan di Prato (UD), Campanotto Editore, 1996.

RICOEUR Paul, Tempo e racconto 2. La configurazione nel racconto di finzione, [1984], Milano, Jaca Book, 1994.

RICOEUR Paul, Tempo e racconto 3. Il tempo raccontato, [1985], Milano, Jaca Book, 1988.

SCARUFFI Piero, Guida all’avanguardia e New Age, Milano, Arcana Editrice, 1991.

VALLI Bernardo, Lo sguardo empatico. Wenders e il cinema nella tarda modernit´, Urbino, Edizioni Quattroventi, 1990.

VALLIER Dora, L’arte astratta, Milano, Garzanti, 1984.

WORRINGER Wilhelm, Astrazione ed empatia, [1908], Torino, Einaudi, 1975.

Websites

CAMPA Riccardo, Dal postmoderno al postumano: il caso Lyotard, in Letteratura-Tradizione, volume 42, 2008, https://ruj.uj.edu.pl/xmlui/handle/item/58854

http://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/