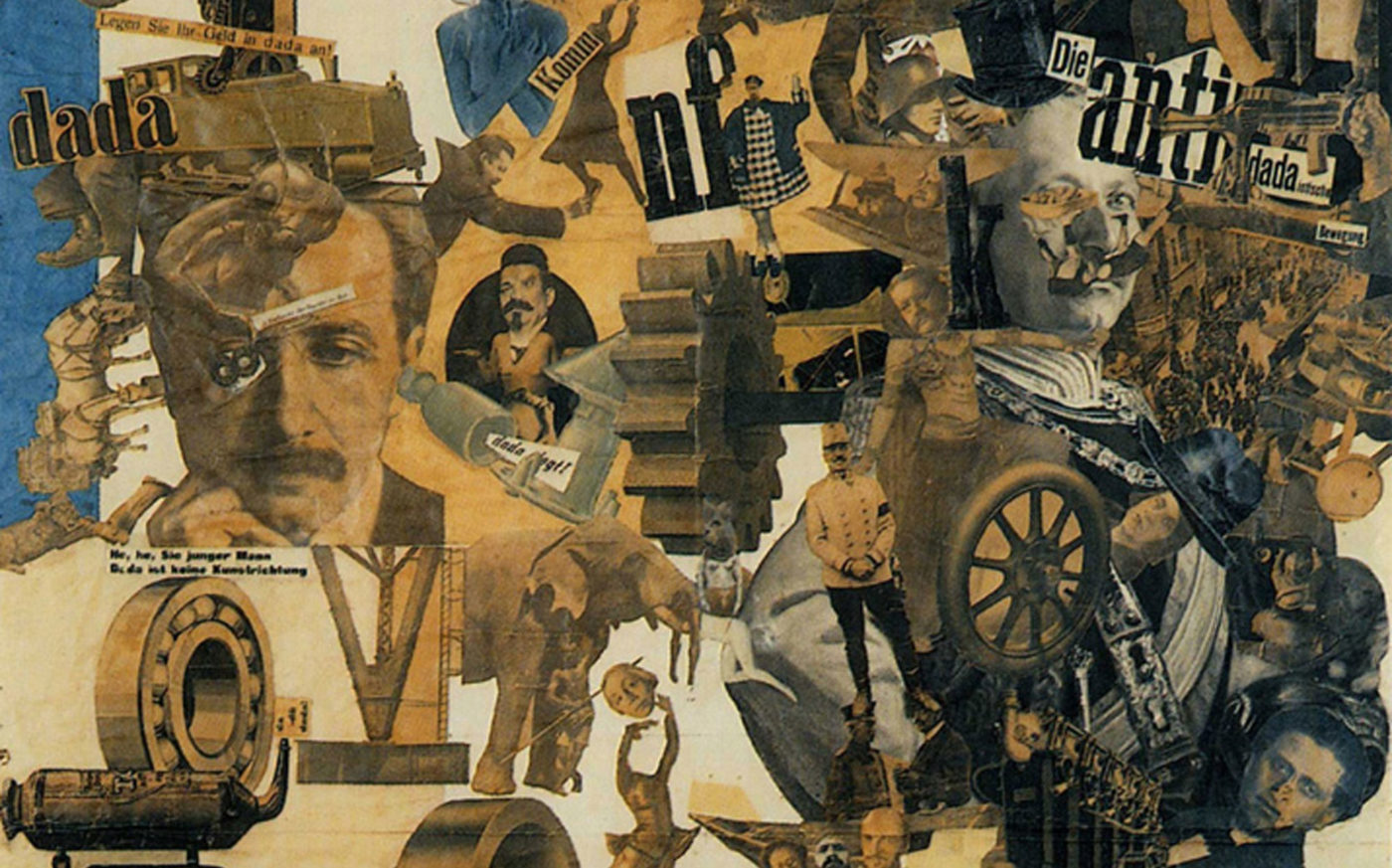

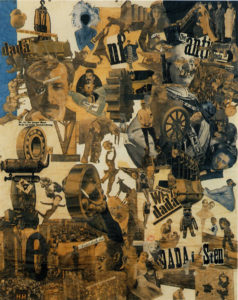

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic (particolare), 1919, collage of pasted papers, 90 x 144 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

In 1916, in Zurich, Dadaism was born, a current that belongs to the group of the so-called historical avant-gardes that marked and revolutionized the artistic scene of the first thirty years of the twentieth century. Certainly Dada, as the name already testifies, with its strong playful component and dubious origin, is among the artistic avant-gardes of the twentieth century the most transgressive and irreverent. That same ironic component, already intrinsic in the nominal identity, is the foundation and the engine that allows it to unhinge any form of language, starting, of course, from the visual and non-visual artistic ones.

In this process of dismantling language, Dadaism intersects both the terrible rise of Nazism and the technical evolution of photography. It will be clear to anyone how, while Hitler’s dictatorial thought and power is making its way, it was complex for an artist to denounce and take a stand against the events triggered by Nazism. The Dadaist will to denounce finds a powerful answer precisely in the encounter with the new photographic language that, also subjected to the playful action typical of this current, leads to the composition of photographic fragments of different origins, thus giving rise to the photomontage. But the photomontage created by Dadaism is also imbued with the cunning and ironic irreverence typical of the bad boy: it uses, in fact, the same photographic materials designed and originally made as tools of the Nazi propaganda spread through the press. So that the denunciation is proffered by the same elements that constituted the propaganda. In short, Raoul Hausmannn (1886-1971), Hannah Höch (1889-1978) (1), John Heartfield (1891-1968), Max Ernst (1891-1976), etc., short-circuit the language of the regime, leading it to its opposite, an operation that in itself is of a biting irony, precisely because it dismantles the language of power from the inside, subverting its grammars and undermining its meanings and signifiers. In essence, if power manipulates truth to create its own propaganda, Dadaism manipulates the falsity of power to lead it back to truth.

Now, who belongs to my generation, and having an imaginary forcibly marked by television communication, has for years witnessed (in Italy) a similar process of short-circuiting of the media language. Maybe he didn’t do it consciously, but in fact he has enjoyed for years, and still today, a process of irreverent criticism of the statements produced by power through television broadcasting and quite similar, in the manner, to that originated many years before by Dadaism. This hereditary repetition was indeed able to originate precisely thanks to the previous Dadaism, to the point of constituting a greater diffusion and normalization of it. I am referring to the program created by Enrico Ghezzi (1952) and Marco Giusti (1953), Blob (2) on air since 1989, whose title is already a manifesto of his intentions. Some will remember the science fiction film of the same name (The Blob of 1958, directed by Irvin Shortess “Shorty” Yeaworth, Jr.), from which the program takes its title, where the Blob is made up of a shapeless and jelly-like mass that devours humans increasing its size from time to time and that, Ghezzi and Giusti, seem to put in parallel with the continuous flow of imaginary produced by television that devours and feeds on the minds of viewers and that, always through them, increases its volume of propagation and power.

(2) Blob, di tutto di più, in onda dal 17 aprile 1989

The program consists of a collage of excerpts from different television broadcasts: variety, news, quizzes, etc.. The sequentiality of the fragments orders a narrative inverse to the one of origin, so that Bruno Vespa, or whoever for him, reveals the truth hidden in the lie profused by the media.

Ghezzi and Giusti, therefore, have transposed an instrument of denunciation, and at the same time of resistance to the propaganda power, from one medium to another. They are certainly not the only ones to have practiced this type of operation: on closer inspection, in fact, television and advertising continuously draw on the linguistic subversions brought by art to maintain the high level of attention of users and to dress themselves in an innovation that is only apparent.

Bibliography

ARGAN Giulio Carlo, L’arte moderna 1770/1970, [1970], Firense, Sansoni Editore, 1982.

ARNHEIM Rudolf, Arte e percezione visiva, [1954], Milano, Feltrinelli, 2002.

BARILLI Renato, Il cilclo del postmoderno. La ricerca artistica degli anni’80, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1987.

BORDONI Carlo FOSSATI Franco, Dal feuilleton al fumetto. Generi e scrittori della letteratura popolare, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

BRANCATO Sergio, Fumetti. Guida ai comics nel sistema dei media, Roma, Datanews Editrice, 1994.

CALVESI Maurizio, Le due avanguardie. Dal Futurismo alla Pop Art, Bari, Laterza, 1991.

CAROLI Flavio, Magico primario, Milano, Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri, 1982.

CASETTI Francesco DI CHIO Federico, Analisi del film, Milano, Bompiani, 1990.

COSTA Antonio, Il cinema e le arrti visive, Torino, Einaudi, 2002

DE MICHELI Mario, Le avanguardie artistiche del Novecento, [1986], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1988.

DE VINCENTI Giorgio, Andare al cinema, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

DE VECCHI Pierluigi CERCHIARI Elda, Arte nel tempo, [1991], Milano, Bompiani, 1996.

DEL GUERCIO Antonio, Storia dell’arte presente, Roma Editori Riuniti, 1985.

DORFLESS Gillo, Ultime tendenze nell’arte d’oggi, [1961], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1985.

FARNÉ Roberto, Iconologia didattica – le immagini per l’educazione dell’Orbis Pictus a Sesame Street, [2002], Bologna, Zanichelli Editore, 2006.

GOMBRICH, Ernst H. HOCHBERG Julian BLACK Max, Arte percezione e realtà, [1972], Torino, Einaudi, 2002.

HARVEY David, La crisi della modernità, [1990], Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1997.

HONNEF Klaus, L’arte contemporanea, Köln, Taschen, 1990.

HUGHES Robert, Lo shock dell’arte moderna, Milano, Idealibri, 1982.

KUBLER George, La forma del tempo, [1972], Torino, Einaudi, 1989.

MENNA Filiberto, La linea analitica dell’arte moderna, [1975], Torino, Einaudi, 1983.

SWEENEY Michael S., Dentro la Mente – La sorprendente scienza che spiega come vediamo, cosa pensiamo e chi siamo, Vercelli, Edizioni White Star (per l’Italia), National Geographic Society, 2012

TORNAGHI Elena, Il linguaggio dell’arte, [1996], Torino, Loescher, 2001

VALLIER Dora, L’arte astratta, Milano, Garzanti, 1984.

Siti web