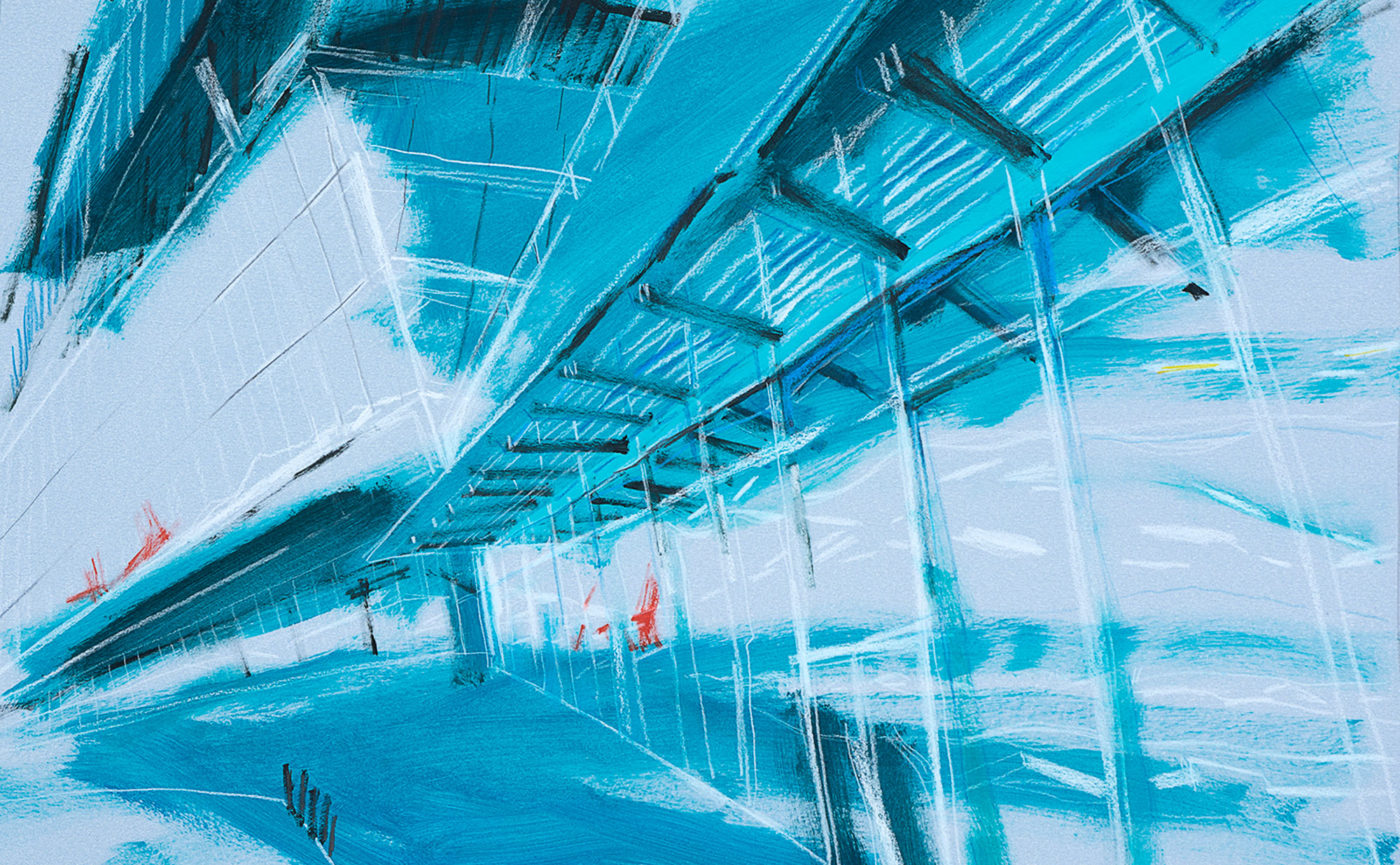

Helen Shulkin, Vancouver Cruise Terminal II, 2018

Post-urbanity

Technological evolution has changed urban objects. Many urban spaces have lost their previous function like postindustrial areas and many urban objects are influenced by a postmodernism, and should be therefore be defined as post-urban spaces and objects. Posturbanity reveals new strata of recent sociological, cultural and technological developments. Some of its architectural identities deepened into the style of neofuturism and some into the structural expressionism like hightech architecture.

These changes force many street and urban artists to find new ways of expression because many postmodern buildings have no conventional walls. But the most important question is how the posturban processes in the modern city can be interpreted by an artist who is working with traditional media? How to find which objects represent the conflict between old and new, which urban spaces are most susceptible to change, what are the prevalent portrayals of postobjects, how are those transformations perceived in human awareness, and which technological structures maintain their entity. How to capture the transformation of the future city? In this context, a fundamental question arises: does the city have a quintessence or hypostasis to extract and portray?

Giovanni Battista Piranesi extracted such a quintessence of the city in his 1749 engravings series called “Carceri”. In this series, he depicted architectural constructions that were frightening in their size and lack of comprehensible logic, where spaces are mysterious, as the purpose of these staircases, bridges, passages, blocks and chains is not clear. The power of stone structures suppresses. Creating the second version of the “Carceri”, the artist has dramatized the original compositions: deepened the shadows, added many details and human figures – like prisoners. In fact, Piranesi has cracked the Pandora’s box and released architectural giants as anticipation of architectural postmodernism…

After 200 years, Piet Mondrian arrives in New York and plunges into the atmosphere of Manhattan, and then creates such canvases as the “New York City” and “Broadway Boogie Woogie”. The quintessence of the city of Piet Mondrian is presented in a very different light than that of Piranesi. It’s an endless jazz, an endless rhythm of racing taxis… His paintings are made up of simple coloured surfaces, where the sensual centre of the city is extremely simplified and reduced, where the balance between the individual and the universal is created. As a result, Piet Mondrian opened the Pandora’s box and released the music, enclosing it in his squares and rectangles, as if fearing that it would escape…

Two completely different artists, who lived in different eras, in their own way opened up the identity of the city. However, the city changes and experiences deep transformations. It is time to reopen the Pandora’s box…

Helen Shulkin

Bibliography

Blotkamp C., Mondrian: The Art of Destruction, 1994

Bloober J., Architecture and the Text: The (S)crypts of Joyse and Piranesi, 1993

Post-urbano

L’evoluzione tecnologica ha cambiato gli oggetti urbani. Molti spazi urbani hanno perso la loro funzione precedente come le aree post-industriali e molti oggetti urbani sono influenzati dal postmodernismo, dovrebbero quindi essere definiti spazi e oggetti post-urbani. Il post-urbanesimo rivela nuove stratificazioni di recenti sviluppi sociologici, culturali e tecnologici. Alcune delle sue identità architettoniche si sono sviluppate nello stile del neo-futurismo, altre, in quello dell’espressionismo strutturale come l’architettura high-tech.

Questi cambiamenti costringono molti artisti di strada o urbani a trovare nuovi modi di esprimersi perché molti edifici postmoderni non hanno muri convenzionali. Ma l’aspetto più importante è come i processi post-urbani nella città moderna possono essere interpretati da un artista che lavora con i media tradizionali. Come trovare gli oggetti che rappresentano il conflitto tra vecchio e nuovo, quali sono gli spazi urbani più suscettibili al cambiamento, quali sono le rappresentazioni prevalenti dei post-oggetti, come vengono percepite quelle trasformazioni nella coscienza umana e quali strutture tecnologiche mantengono la loro entità. Come cogliere la trasformazione della città futura? In questo contesto, sorge una domanda fondamentale: la città ha una quintessenza o un’ipostasi da estrarre e ritrarre?

Giovanni Battista Piranesi ha estratto tale quintessenza della città nella serie d’incisioni dal titolo Carceri del 1749. In questa serie ritrae costruzioni architettoniche spaventose nelle dimensioni e nella mancanza di una logica comprensibile, dove gli spazi sono misteriosi, poiché non è chiaro lo scopo di queste scale, ponti, passaggi, blocchi e catene. Il potere delle strutture in pietra opprime. Creando la seconda versione delle Carceri, l’artista ha drammatizzato le composizioni originali: ha approfondito le ombre, ha aggiunto molti dettagli e figure umane (come prigionieri). Piranesi, infatti, ha rotto il vaso di Pandora e liberato giganti architettonici come anticipazione del postmodernismo architettonico.

Dopo 200 anni, Piet Mondrian arriva a New York e s’immerge nell’atmosfera di Manhattan, per poi creare tele come New York City e Broadway Boogie Woogie. La quintessenza della città di Piet Mondrian si presenta in una luce molto diversa da quella di Piranesi. E’ un jazz senza fine, un ritmo infinito di taxi da corsa. I suoi dipinti sono costituiti da semplici superfici colorate, dove il centro sensuale della città è estremamente semplificato e ridotto, dove si crea l’equilibrio tra l’individuo e l’universale. Piet Mondrian apre il vaso di Pandora e libera la musica, racchiudendola nei suoi quadrati e rettangoli, come se temesse che potesse fuggire.

Due artisti completamente diversi, vissuti in epoche differenti, hanno svelato a modo loro l’identità della città. Ma la città cambia e vive profonde trasformazioni. E’ tempo di riaprire il vaso di Pandora.

Helen Shulkin

Bibliografia

Blotkamp C., Mondrian: The Art of Destruction, 1994

Bloober J., Architecture and the Text: The (S)crypts of Joyse and Piranesi, 1993