Caravaggio, Flagellation of Christ, detail, 1607

Light can suggest the volumetric spatiality of subjects, animated or inanimate, and a lasting or temporary temporality of events.

Throughout the history of art, geographical productions have been marked by different types of representation that, from time to time, underwent declinations according to the ages. We would like to compare three of these different typologies in order to differentiate the three different ways of understanding representation, space and time. If we examine a typical work of central Italy from the Renaissance period, such as the Pietà (1483-1493ca.) (1) by Pietro Perugino (Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci, known as Perugino 1446-1523), we notice how light spreads uniformly in every point of the painting, even if we find ourselves in a space partially covered by a loggia with vaulted arches. We should therefore expect a greater use of chiaroscuro due to the shadows brought by the vaults themselves, both on the surrounding environment and on the subjects represented. Yet there is no trace of such chiaroscuro contrasts. The reason is to be traced back to the theme and interpretation that Perugino, and with him the Renaissance painters of that area of production, give subjects of a religious nature. The observations, which we have just made, would be exact if brought back to the presence of natural light. A light that originated from the sun, placed at a certain height and according to the time of day, would produce shadows projected of different lengths, but the light that pervades that pictorial space has a supernatural and divine nature and does not respond, therefore, to physical laws and natural earthly. This pervasiveness of light gives calm and serenity to the environment and an unnatural immobility to the bodies and to the event itself. Everything seems to happen forever and forever, as is appropriate for events of an otherworldly nature. Eternity of time pervades the space of representation.

(1) Pietro Perugino, Pietà, 1483-1493ca.

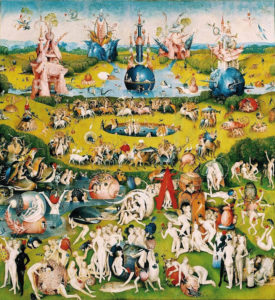

If we now turn our attention to one of the best known and typical examples of Renaissance painting in the Flemish area, painted in the same period by Hieronymus Bosch (Jeroen Anthoniszoon van Aken known as Hieronymus Bosch 1453-1516) (2), it is evident that the pictorial components are profoundly different. It should be noted, first of all, that there is no trace of the typical Italian Renaissance atmospheric system here. Italian painting of this period is invariably pervaded, albeit with different declinations according to the authors and the production areas, by the impalpable presence of the atmosphere, a pictorial rendering of the air that makes the work appear as a space physically passable or passable. The Flemish tradition, on the other hand, seems to renounce this atmospheric emulation; the painting places a greater distance between itself and the viewer, whose gaze travels over the surface but without crossing it, since it does not pretend to be reality, but instead adheres to its two-dimensional nature, where drawing and colour, while referring to anatomical and landscape elements of reality, do not claim to emulate it as physical space. In essence, the Flemish representation reveals its being fiction, not inducing atmospheric or temporal illusion in the viewer. In it, temporality is a completely foreign concept. For this reason all the elements that appear there, even though they have a volume, do not seem to have a physicality and the same colours renounce that soft aspect of the complexion and the aerial impalpability typical of Italian works, to assume instead a more fairy-tale flavor, similar to that which characterizes a modern illustration for children, which certainly has no will, nor utility, to generate physical spatiality.

(2) Hieronymus Bosch, triptych central panel Garden of Delights, 1480-1490ca.

We now make a temporal leap of little more than a century with the Flagellation of Christ (3) painted by Caravaggio (Micelangelo Merisi known as Caravaggio 1571-1610) in 1607. As is well known, in his painting, chiaroscuro contrasts become predominant and tend to swallow up figures and environments, as in Leonardo’s work the surrounding tends to penetrate and overpower the physicality of the subjects. This imprint was also taken by Leonardo to the Lombard area during his stay in Milan at the Sforza court, but if in Leonardo’s work the landscape, representing the natural forces that dominate the cosmos, takes over, in Caravaggio’s painting it is instead the contrast between light and shadow that dominates, almost leaving no trace of other presences that only with difficulty emerge from the shadow. Everything in Caravaggio originates from light, it is the element that allows and gives shape to the narrative. Far from playing a mere role of volumetric rendering of the subjects, light, in his painting, plays first of all a hierarchical action puts in “light” the protagonists of his works, to become then “light” moral and spiritual putting the right in “light” and, finally, representing the temporal presence through the bodies that, with effort and only for a moment, can emerge from the darkness into which they will fall as soon as we turn our eyes. In his work everything happens before our eyes, here and now, the bodies and their action are caught in an instant that is more cinematic than pictorial. This markedly realistic sense of everyday life is amplified by the models portrayed by the painter, common subjects captured from the street, belonging to the disadvantaged classes, prostitutes and hardened players, frequenters of taverns, of which the author himself was an assiduous. Caravaggio thus brought holiness into the low depths of everyday life, a particular aspect that Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975) would treasure in his cinematography more than three centuries later. It is enough to take a look at a film like Mamma Roma (1962) to realize it.

(3) Caravaggio, Flagellazione di Cristo, 1607

Moreover, Caravaggio has always been loved by filmmakers, especially those in the neo-realist area (Neorealism is an Italian film current, active since 1943, which includes among its major filmmakers Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica and Luchino Visconti, to name but three), probably because of his pictorial-cinematographic cut that seems to narrate the events in the space of an instant-photogram, but that seems to refer to a before and an after, even if the before and the after seem to be hidden in the shadow from which events and actions emerge. Caravaggio’s painting is therefore in clear contrast with the Renaissance production of central Italy, to which he opposes the fragment of time to eternity, drama to calm serenity, the everyday life and truth of the subjects to inanimate and frozen figures, the cultured and illuminated action in an instant to the otherworldly immobility where everything remains forever.

Let’s continue with the analysis of the use of light right within the cinema, of which we will bring a first example, taken from the neorealist production, with Roma Città Aperta (1945) (4) by Roberto Rossellini (1906-1977), who seems to have made the most of the lesson of the Lombard painter: the strong chiaroscuro contraposition is that of the Caravaggio matrix, which allows the light to generate the narration, highlighting the positive character compared to the executioners, both hierarchically and morally; and here, the event, is really captured in the instant of the individual frames. In essence, Rossellini uses Caravaggio’s dramatic light to narrate the events of the Nazi occupation in Italy, where the saints are the common citizens who oppose domination and the Nazis the torturers. Rosselini assigns, and expresses with light, the drama and truthfulness of the events.

(4) Roberto Rossellini, Roma Città Aperta, 1945

If we compare Rosselini’s use of light with that of Frank Capra (1897-1991) in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (5) of 1939, it seems, in a certain sense, to find ourselves in that contrast that we have already described between Caravaggio’s painting and that observed in Perugino as a representative of the painting of central Italy. Here, too, the diffused light makes the events narrated and the souls of the observers serene, everything becomes lighter, as befits an entertainment film, where the life narrated resembles an appendix novel rather than life lived. Even before the types interpreted by the actors, with their hairstyles, their costumes, their expressiveness, it is the light that tells us this sweetness and lightness.

(5) Frank Capra, Mr. Smith va a Washington, 1939

In Carefree (6) of 1938 by Sandrich (Mark Sandrich 1900-1945) this gentleness and lightness of luministic matrix is taken to its extreme consequences, an aspect common to musicals, where everything seems to take place on theatrical stages that reproduce scenes of everyday life, but that preserve artificiality and abstraction of the theatricality. The more than diffused light becomes blinding, homogeneously permeating subjects and environments, so as to eliminate “own shadows” and “brought shadows” that would highlight the former’s physical volume and the latter’s gravitational weight. The absence of shadows places us in a realm of heavenly light, where those bodies can float lightly in the air, as if they were able to fly and not just dance. A type of lighting undoubtedly functional to the artificiality of a musical, where suddenly people begin to sing and dance and where those dancing bodies should not have weight, allowing the heavenly serenity of light to give shape to the ultimate entertainment.

(6) Mark Sandrich, Girandola, 1938

Bibliography

ARNHEIM Rudolf, Arte e percezione visiva, [1954], Milano, Feltrinelli, 2002.

BAIRATI Eleonora – FINOCCHI Anna, Arte in Italia, [1984], Torino, Loescher Editore, 1991.

CAROLI Flavio, Magico primario, Milano, Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri, 1982.

COSTA Antonio, Il cinema e le arrti visive, Torino, Einaudi, 2002

DE GRANDIS Luigina, Teoria e uso del colore, Milano, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1984

DE VECCHI Pierluigi CERCHIARI Elda, Arte nel tempo, [1991], Milano, Bompiani, 1996.

DE VINCENTI Giorgio, Andare al cinema, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

GOMBRICH, Ernst H. HOCHBERG Julian BLACK Max, Arte percezione e realtà, [1972], Torino, Einaudi, 2002.

GUGLIELMINO Salvatore, Guida al novecento, [1971], Milano, Editrice G. Principato s.p.a., 1982.

ITTEN Jhoannes, Arte del colore, [1961], Milano, Il Saggiatore, 2001.

KANDINSKY Wassily, Punto linea superficie, [1925], Milano, Adelphi, 1982

LONGHI Roberto, Cravaggio, [1982], Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1994.

MALTESE Corrado, Guida allo studio della storia dell’arte, [1975], Milano, Mursia, 1988.

SCARUFFI Piero, Guida all’avanguardia e New Age, Milano, Arcana Editrice, 1991.

SPIZZOTIN Pierantonio a cura di, Il Quattrocento in Europa, in I secoli d’oro dell’arte, Milano, Orsa Maggiore Editrice, 1988

SWEENEY Michael S., Dentro la Mente – La sorprendente scienza che spiega come vediamo, cosa pensiamo e chi siamo,, Vercelli, Edizioni White Star (per l’Italia), National Geographic Society, 2012

TORNAGHI Elena, Il linguaggio dell’arte, [1996], Torino, Loescher, 2001

VALLIER Dora, L’arte astratta, Milano, Garzanti, 1984.

WORRINGER Wilhelm, Astrazione e empatia, [1908], Torino, Einaudi, 1975.

Website

http://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/