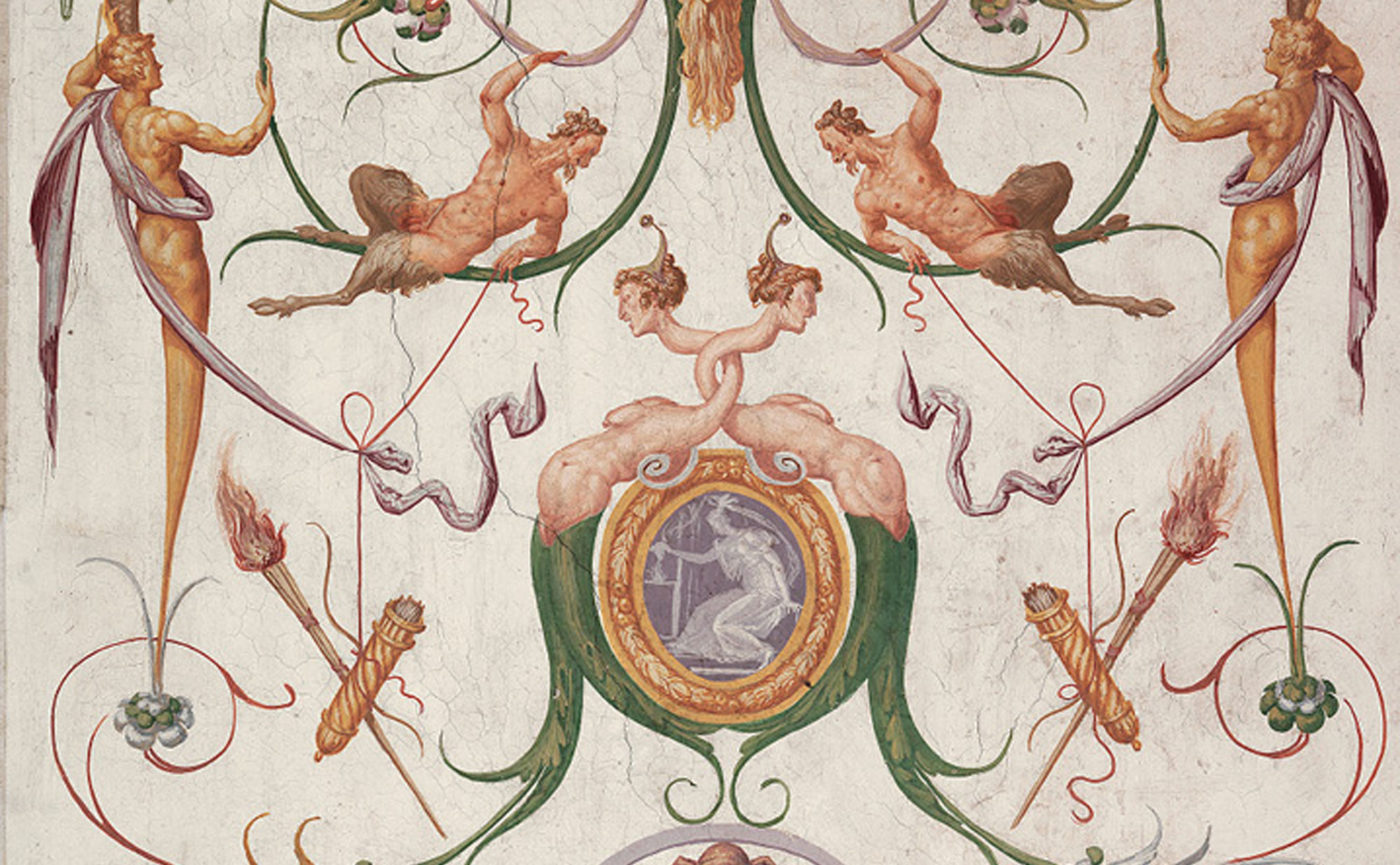

Giovan Battista Zelotti, Allegory of Libra (particolre), Villa Emo in Fanzolo, dressing room of the grotesques, c. 1565.

When the dungeons (caves) of Nero’s Domus Aurea were found in Rome around 1480, the effect on the painters of the time, and Raphael in particular, was a harbinger of unstoppable changes for the future visual alphabet. Those caves had, in fact, wall decorations which combined arboreal and floral elements with animal or human presences, often giving rise to beings of hybrid nature, whose effect could be funny or “grotesque”, as we say today, but at the same time monstrous and disturbing. From that moment on, the so-called “grotesque” (cave) decoration came into vogue, which widely proposed that type of decoration in noble palaces, thus laying the linguistic foundations of the future baroque bizarreness that, in turn, will pour into the next Rococo. But the reflexes of that discovery did not only reverberate on those more known and evident artistic manifestations, their “grotesque” aspect led to more unexpected directions, giving rise, from the last twenty years of the sixteenth century, to a conspicuous production of drawings that we would later call caricatures, whose birth is often traced back to the early seventeenth century and Annibale Carracci, but which had ample space in the work of many Italian and foreign artists. If we then look at Leonardo’s grotesque studies, we understand that everything was already in place for some time. Particular mention should be made of the visionary work of Bracelli (Giovan Battista Bracelli 1584-1650), extraordinary creator of hybridizations and anthropomorphizations. If, in fact, Carracci gave shape to the caricature that today we would define more classic, Bracelli animated an infinite series of man-plant, man-object, man-metal forerunners of the later science fiction automatons. Without forgetting, of course, the hilarious characters from the drawings of Jacque Callot (1592-1635) or Baccio del Bianco (1604-1656), which of course were followed by many others: Stefano della Bella (1610-1664), Pier Francesco Mola (1612-1666), Giuseppe Maria Mitelli (1634-1718), Giovan Battista Gaulli (1639-1709), Pier Leone Ghezzi (1674-1755), Anton Maria Zanetti (1680-1767), Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770), William Hogarth (1697-1764), Giandomenico Tiepolo (1727-1804), Francisco Goya (1746-1828), James Gillray (1756-1815), Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827), George Cruikshank (1792-1878), Grandville (1803-1847), C. J. Traviés (1804-1859), Paul Gavarni (1804-1866), Honoré Daumier (1808-1879), John Leech (1817-1864), to name but a few.

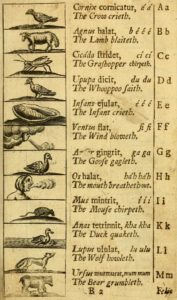

All this was followed, as has been said, by the Baroque and then the Rococo, leading us into the eighteenth-century body. Twenty years before the discovery of the fateful caves, in the meantime, the press was born and these two phenomena – linguistic development triggered by the grotesques and the birth of the press – intersected in this very century in the first forms of what we could define the alphabet of illustration as we understand it today. Those who would like to trace the origin of illustrations back to illuminated manuscripts, or even earlier, have certainly not understood how the nature of illustration is intrinsically linked to the development of publishing and its expressive needs – as well as to the development of printing techniques – which were primarily of a didactic nature. After all, the term “illustration” itself was born only in 1817 in England and then passed to France in the middle of the same century and arrived in Italy only in 1869. Its very name testifies to its vocation to accompany, to make explicit and make evident something that the text alone would not be able to express. It is obvious that here we are referring to what we are today used to call fiction illustration, that is to say, to all that illustration that addresses contexts of fiction and not only editorial fiction. But, as mentioned above, its didactic vocation arose in 1658 with the Orbis Sensalium Pictus by Giovanni Amos Comenio, who wrote the forerunner of all abecedaries in an attempt to facilitate alphabetical learning in children. Thus starting the other side of illustration called instead of non-fiction, which addresses the contexts of an informative nature, whose first aspect had already arisen with the investigations on the human body already undertaken by Leonardo in the Renaissance. This aspect of illustration, with a clear scientific information purpose, is therefore previous. Consequently, the birth of the so-called non-fiction is prior to that of fiction, both in its informative-scientific identity and in its informative-educational and didactic one. Although mention should be made of Ulrich Boner’s Der Edelstein of 1456, a collection of illustrated fairy tales published shortly after the birth of the press.

Giovanni Amos Comenio

Giovanni Amos Comenio  Ulrich Boner

Ulrich Boner

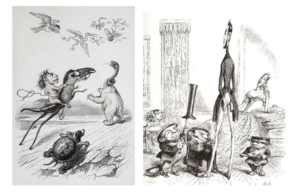

If we now return to the alphabetical roots of the linguistic apparatus that is inextricably linked to fiction, we see how the century of the Enlightenment, the eighteenth century, is the century that gives birth to illustration for many reasons and concomitances, all dictated by the didactic and diffusive will of knowledge typical of the Enlightenment. A will that determined the start of schooling and the consequent increase in the number of readers and, of course, the proliferation of publishers and their need for more modern printing techniques that would allow an increase in the number of copies at less time and cost, not only in the book but also journalistic direction. It is, in fact, this logic that gives rise to the organs that we define today of information and that, not being able then to be accompanied by photography, made massive use of the work of designers specialized in accompanying articles of social and political current affairs, so the previous caricature became the basis of today’s humorous-irreverent cartoons. As a matter of course, the first illustrators who applied themselves were painters and so it was for a good part of the following nineteenth century, but during that century the figures specialized in illustrating those editions multiplied out of all proportion, marking, as a consequence, the progressive separation of the two professions. Many newspapers of the time were born with a humorous vocation, making caricature their strong point and the illustrators applied themselves to it and developed the alphabet in increasingly modern terms, finding original formal solutions, in turn harbingers of subsequent imaginative universes. Suffice it to mention here the case of Grandville, forerunner of many successive imaginaries. His formal forcing gave life to a conglomeration of anthropomorphic characters, which, from the root of the Grotesques, can lead us to the Disney imagination, passing obviously through Beatrix Potter. But his anthropomorphism, not only of animal nature but also of object derivation (and here we find Bracelli), anticipates part of the figurative production of Surrealism, as well as his anatomical forcing that deform the characters as in a hall of mirrors of the amusement park. Moreover, he goes into new and daring pre-comic and pre-cinematographic shots.

Grandville

Grandville

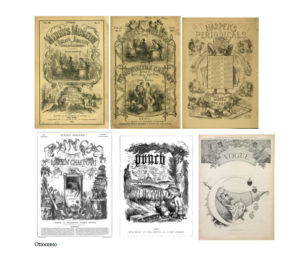

It is still within this logic that the literary genre or paraletteratura was born, which saw, first of all, a wide proliferation precisely in periodicals and subsequent editions of fine books. Forerunner is The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole in 1764, the first example of a Gothic novel. A better known example is the Frankenstein or the modern Prometheus written by Shelley in 1818, which contains within it the seeds of the future literary genres of science fiction and horror. Within those periodicals there is also ample space for women’s literature, and even here, multiplying the number of women readers, the specialized publishing industry will not fail to give a prompt answer to this new question with the so-called sentimental novel. The evolution of fiction illustration is, in fact, intimately linked to the development of literary genres.

All this, as is well known, came about as a result of the rise of the bourgeoisie over the nobility, which, thanks to the wealth it was accumulating as a result of the Industrial Revolution, supplanted it. In France, meanwhile, a revolution of a political-social order is underway that will lead, with various vicissitudes, to the emancipation of the bourgeois class. An emancipation originating from that Enlightenment thought devoted to the diffusion of knowledge, whose most famous manifestation is the writing of the Encyclopédie ou dictionaire raissoné des sciences, des artes et des métieres by Diderot and D’Alembert. Vocation that does not leave out any ravine of human knowledge, questioning the prison and social systems, the historical roots of human culture and civilization, giving rise to archaeology also in conjunction with the extraordinary excavations of Herculaneum started in 1748, the analysis of different cultures and civilizations with the founding of ethnology in 1783. But the unbridled positivist optimism laid its foundations and its evolution on the proceeds of the Industrial Revolution, which, as another side of the coin, gave rise to economic capitalism whose nature could not but clash against the drive for popular emancipation, and so, as we know, the first mass and social political movements were born: socialism (precisely) and communism.

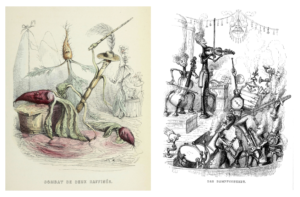

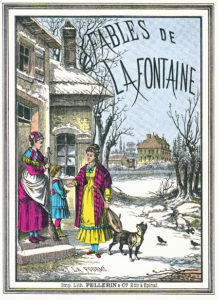

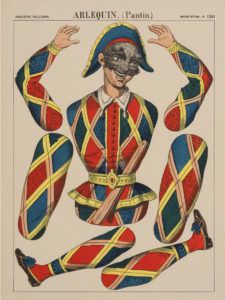

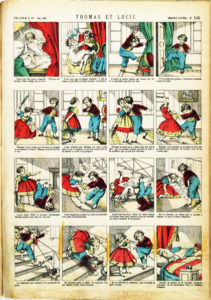

It is within this editorial logic, which is about to become an industry, that the Imagerie d’Epinal was born in the eighteenth century. The printing company founded by Jean-Charles Pellerin in 1796, precisely in Epinal, and tireless producer of popular images, within which the imaginative formal vocabulary that was to be fundamental for the alphabetical evolution of illustration and later for that of comics was born. Pellerin paid particular attention to products aimed at children, offering games, models to be cut out, fold and build, illustrated toy soldiers, famous novels and rigorously illustrated fairy tales, thus creating both the toy industry and illustrated children’s publishing. That formal alphabet could only derive from the previous caricatured forcing, which in turn sprang from the bizarre things found in the dungeons of the Domus, later to become Grotesque.

Imagerie d’Epinal

Imagerie d’Epinal

Just as the discovery of the caves of the Domus gave rise to the grotesques, so did the emergence of the archaeological treasures of Herculaneum, and later Pompeii, gave rise to Neoclassicism, which in the interior applications and furnishings proposed the decorative samples already partly belonged to the grotesques. Thus, the disturbing and monstrous elements of that decorativism flowed into the visionary nightmares of the Gothic period, but pervaded by a dark, typically medieval atmosphere, as were the settings of the novels of the genre. Those horrifying and alienating creatures will never again abandon our imaginary, creeping in everywhere, even in the nightmares of the last Goya.

Equally insinuating became the vegetal and floral decorativism that at the end of the nineteenth century was revealed in Art Nouveau, as well as in the graphic design of many book publishing since the eighteenth century. But alongside Liberty, to renew the magical-esoteric nightmares, symbolism made its way.

That young man who at the end of the fifteenth century climbed the Oppio Hill, falling into a frescoed cave, as the narrative goes, would certainly not have believed that his accident could change our history and our imaginary and, with them, the idea that until then had been preserved of antiquity, which, from sober and faded suddenly became sumptuously colorful and not so rational and balanced.

Bibliography

ARGAN Giulio Carlo, L’arte moderna 1770/1970, [1970], Firense, Sansoni Editore, 1982.

BAIRATI Eleonora FINOCCHI Anna, Arte in Italia, [1984], Torino, Loescher, 1991.

BORDONI Carlo FOSSATI Franco, Dal feuilleton al fumetto. Generi e scrittori della letteratura popolare, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

BRANCATO Sergio, Fumetti. Guida ai comics nel sistema dei media, Roma, Datanews Editrice, 1994.

CAROCCI Giampiero, Elementi di storia – L’Età delle rivoluzioni borghesi, volume 2, [1985], Bologna, Zanichelli, 1990.

CHASTEL André, La Grottesca, Torino, Einaudi, 1989

DE VECCHI Pierluigi CERCHIARI Elda, Arte nel tempo, [1991], Milano, Bompiani, 1996.

DORFLESS Gillo, Ultime tendenze nell’arte d’oggi, [1961], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1985.

FAETI Antonio, Guardare le figure, [1972], Roma, Donzelli Editore, 2011.

FARNÉ Roberto, Iconologia didattica – le immagini per l’educazione dell’Orbis Pictus a Sesame Street, [2002], Bologna, Zanichelli Editore, 2006.

FAVARI Pietro, Le nuvole parlanti. Un secolo di fumetti tra arte e mass media, Bari, Edizioni Dedalo, 1996.

GUGLIELMINO Salvatore, Guida al novecento, [1971], Milano, Editrice G. Principato s.p.a., 1982.

HARVEY David, La crisi della modernità, [1990], Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1997.

HUGH Honour, Neoclassicismo, Torino, Einaudi, 1980

HUGHES Robert, Lo shock dell’arte moderna, Milano, Idealibri, 1982.

KUBLER George, La forma del tempo, [1972], Torino, Einaudi, 1989.

MENNA Filiberto, La linea analitica dell’arte moderna, [1975], Torino, Einaudi, 1983.

PALLOTTINO Paola, Storia dell’illustrazione italiana, [2010], Firenze, VoLo Publisher, 2011.

Websites